The 2023 Dance Magazine Awards Celebrated the Power of Dance to Transcend Barriers

Watching this year’s Dance Magazine Awards ceremony at 92NY (sponsored by 92NY, University of the Arts, and The O’Donnell-Green Music and Dance Foundation), I was reminded of something Lar Lubovitch said in his acceptance speech in 2016: “I am not really sure why we dance, but it appears to be part of human nature that our bodies take over when something inexpressible needs to be said.” With a wide range of spoken, signed, and movement languages, the 2023 awards celebrated the singular contexts and voices of the awardees, all of whom are connected by their dedication to the field of dance—and, in keeping with the theme of this year’s awards, dance education. There was a pervasive sense of welcoming and embrace from the audience as honorees named and thanked family, teachers, friends, students, and supporters; as editor in chief Caitlin Sims commented, “One of my favorite part of the Dance Magazine Awards is seeing the warmth, enthusiasm, and love with which the dance community supports each other.”

The evening kicked off with the Harkness Promise Awards, presented by Harkness Foundation for Dance executive director Joan Finkelstein. Awarded to dance artists within the first decade of their choreographic career, Promise Awards include an unrestricted $5,000 grant and 40 hours of studio space (funded by the net proceeds from the Dance Magazine Awards) with no requirement for a final product. “I will ask the people in the front row to make sure your legs are close to your chairs,” Finkelstein warned with a smile before recipients Baye & Asa (Amadi “Baye” Washington and Sam “Asa” Pratt) took to the stage to perform an intense, athletic, arresting duet from their Collective Bargain. This was followed by filmed excerpts of recipient Omar Román De Jesús’ choreography performed by his company Boca Tuya, Bruce Wood Dance, and BalletCollective, showcasing slippery partnering and theatrical, offbeat imagery.

Finkelstein praised Baye & Asa for their work in which they “create political metaphors, interrogate systemic inequities, and contemporize ancient allegories,” as well as “for building theatrical contexts that simultaneously celebrate, implicate, and condemn the characters onstage, and for your courage and heart in confronting our contemporary reality of violence while communicating the absolute necessity for empathy.” During their acceptance speech, Pratt reflected, “In a contemporary world, there’s a lot of pressure to put yourself into a camp, to distill, succinctly and uncompromisingly, what you believe and where you stand. I think dance is uniquely positioned as an art form that can liberate thought into indeterminacy and to widen toward multiplicity instead of narrowing towards one singular thesis. Art remains one of the most advanced pieces of technology we have as a species.”

Presenting to De Jesús, Finkelstein said he was being recognized for his choreography “that blends virtuosity and naturalism to mine issues of identity, love, queerness, injustice, Latinidad, and the quest for community and agency, and for articulating and implementing Boca Tuya’s mission to create visibility for, support, and uplift emerging Latinx dance artists and choreographers.” In accepting the award, De Jesús said, “As artists, it is vital that we hold on to the hope of our own promise. As we strive for visibility and the capacity to dream without boundaries,” he hoped that we would continue to ask each other the questions that he said have granted him his success and visibility: What do you need? What do you want? How can I help you?

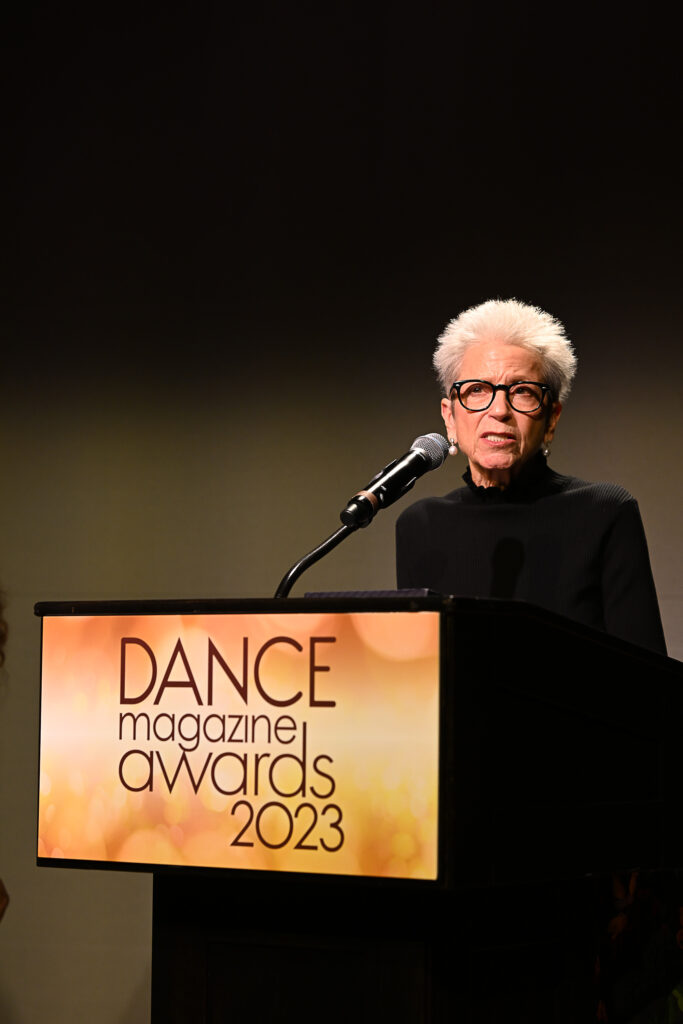

The evening moved from looking to the future to looking to the past, as editor at large Wendy Perron spoke about the dance artists who were recognized with the first posthumous Dance Magazine Awards. “I’ve been so immersed in dance history, in both my teaching and my writing,” Perron said, “that the four people I’m about to tell you about are very much alive for me.” While tracing their biographies, Perron lovingly illuminated lesser known connections of these well known figures—Syvilla Fort’s collaboration with John Cage when she was a student leading to Cage’s innovation of prepared piano; Gregory Hines’ influence on Savion Glover, Dianne Walker, and Jason Samuels Smith (all Dance Magazine Award recipients); Pearl Primus being pointed to the New Dance Group by a fellow student at Hunter College—Perron’s mother; Helen Tamiris choreographing the 1946 revival of Showboat, in which Primus had the top dancing role—and the impact they had in the words of their contemporaries and biographers.

Harlem Stage managing director Eric Oberstein spoke in honor of Bijayini Satpathy after a video excerpt of her Call of Dawn, which showcased the Odissi artist’s marriage of imagination with technical mastery and seemingly effortless musicality. Oberstein, who began working with Satpathy when he worked at Duke Performances and she was a principal at Nrityagram, recalled being stunned when a few years later, she chose to leave Nrityagram, and was unnerved to see a hint of nervousness from such a preternaturally calm person. He recounted the subsequent process of producing Satpathy’s critically acclaimed solo show ABHIPSAA: A Seeking, concluding, “She has taught me that it’s okay to not always know what lies beyond the horizon, but to trust in what you can bring to this world that is uniquely you.”

Satpathy was unable to attend the ceremony, but recorded an acceptance speech from her home in India. “Odissi, to me, now belongs to the world,” she said. “Like any other dance, it has its specific cultural roots. What is very precious and beautiful about Odissi, even though it is deeply rooted in its tradition, is it offers an expanded capacity of imagination, beyond time, beyond borders, beyond its cultural specificity. To have worked with its expanded capacity in education and training, in choreography and performances, has been a great, great blessing and privilege.” She accepted the award on behalf of all practitioners, gurus, custodians, scholars, and architects of Odissi of the past and present.

A half-dozen dancers turned up the temperature with a high-energy performance excerpted from Maria Torres‘ The Pan-American Nutcracker Suite—Reimagined, showing off rapid-fire footwork and gleeful partnering. Tony nominated actress Daphne Rubin-Vega was on hand after to present to Torres. Rather than run through the groundbreaking choreographer’s career and accomplishments (“You can Google who Maria Torres is,” Rubin-Vega drawled), she shared that when she and Lin-Manuel Miranda were doing promotion for In the Heights, an interviewer asked Miranda about what impact Rubin-Vega had on him, as the first Latina performer he saw on Broadway. “Lin said, ‘Well, Daphne was not the first I saw on Broadway. It was Maria Torres,’ ” Rubin-Vega said. “It made me fizz up with joy, to know that we stand on the shoulders of those that came before. In no uncertain terms, when all doors were closed, this is a sister who created jobs and opportunities for others who looked like me, and who didn’t look like me. I am here on purpose. And that is because of Maria Torres.”

After taking to the podium, Torres said, “I’m reminded of the journey that brought me to this moment. A journey that filled me with dreams, challenges, and the unwavering belief that dance can transcend barriers and transform lives.” She recalled eagerly paging through Dance Magazine as a teenager, imagining herself at a podium like this one, “speaking about my heritage, and my body type, which did not conform to the norm.” She showed off her sparkly, curve-hugging dress, which she had selected for the occasion for just that reason. Torres also credited her husband with rekindled her love for dance and her career at a point where she was ready to walk away, and late Ailey School director Denise Jefferson for supporting and comforting her when she was struggling with the death of her mother. She concluded with a pledge “to continue my lifelong commitment to dance education, to strive for excellence in all that I do, and to inspire and empower future generations of dancers,” and noted that her mother had made her promise two things: to teach, and, when she made it up to that podium, to speak Spanish—which Torres did.

Antoine Hunter PurpleFireCrow performed his Beat of Earth alongside members of his Urban Jazz Dance Company, standing downstage to sign Michael Jackson’s “Earth Song” while five dancers embodied the epic, emotional track. President and CEO emerita of the International Association of Blacks in Dance Denise Saunders Thompson, presenting Hunter his award in a poetic, deeply felt speech, said, “Dance runs deep in his body. Dance has served him well. It has been a vehicle that has opened doors, broken down barriers—probably put some into place as well—and provided a language to communicate beyond the spoken word. His choreography transcends his persona: Black, Indigenous Blackfoot and Cherokee, Deaf, disabled, two-spirited. Antoine Hunter listens with his body and his heart. Antoine frees us with his rhythm, his style, his sensuality, his musicality, his fullest self—that’s his superpower.” Saunders Thompson invited the audience to imagine the life he has led in a hearing world, concluding, “We can learn so much more from Antoine Hunter.”

Hunter’s acceptance speech, interpreted from American Sign Language by Rorri Burton (who shared ASL interpretation duties with Selena Flowers throughout the evening), began with the dance artist thanking Thompson for her support. “You have welcomed me in the Black family. We all need a home. Thank you for being that home.” He reintroduced himself by teaching the audience his sign name before explaining how dance saved his life. “When you can’t express yourself,” he signed, “you can feel like you’re losing your mind. You’re not able to make those connections. When someone is finally able to listen to you, you find a place where you feel at home.” He continued that, “Just because you have the ability to hear, does not mean you know how to listen. You have to learn to listen. It happens with your heart, with your spirit. It happens when you’re understanding where someone is coming from. Open your mind. Open your heart. Open your spirit.” He encouraged everyone watching and listening to know that everyone has a story worth telling, and if you don’t see other people like you out in the world, to create the space you want to see so others can find you and build a home together. “Folks in the Deaf community and in the disabled community bring more power to the dance community as a whole. We don’t want to be a token, we don’t want to be here and gone. We want to build family.”

In honor of Alicia Graf Mack, recent Juilliard graduates Rachel Lockhart and Waverly Fredericks—both from the first class admitted by Graf Mack after she took the helm of the school’s dance division five years ago—performed River, choreographed by Lockhart. Before beginning to list Graf Mack’s many accomplishments, the indomitable Judith Jamison asked wryly, “How many things can you do in the short time you’ve been on this earth? It’s amazing.” The artistic director emerita of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater recalled, laughing, how Graf Mack came to her shortly before she was meant to sign a contract to dance with Ailey and told her that her heart was still with Arthur Mitchell and Dance Theatre of Harlem.

But when she finally joined Ailey, Graf Mack didn’t rest on her laurels, throwing herself into modern dance technique so she could dance everything from Hans van Manen to Rennie Harris. “If any challenge threatens to stop her all-encompassing trajectory,” Jamison said, “she comes in and out of it stronger, daring you to get in the way of her traveling 32 fouettés.” Jamison praised Graf Mack’s grace and grit, and how she embodies caring about dance, its future, and transmitting that it’s about more than just steps. “I wish I could be around for another hundred years and see what else you’ll do.”

Graf Mack thanked “the queen diva” Jamison for being her north star and for welcoming her into Ailey, which “reminded me daily that we represent something larger than ourselves.” She remembered telling her parents, “I want to dance professionally so badly that if Arthur Mitchell wants me to be a tree in the background for the next 10 years, I am going to be the best dang tree he has ever seen.” She also recounted being a painfully shy child, “but I knew even then I had a superpower. I could move people, touch them, transform their hearts, engage their imagination, and transform a moment with movement.” She recalled the teachers and mentors who said “yes” to her, and her thought that she would never teach herself because she knew the dedication it takes to raise a dancer. “I thought performing was my purpose, my calling. Nope,” she giggled. “Now I know being a teacher or a mentor behind a young person’s inspired performance, or just seeing an ounce of your spirit living in them, is the most enduring affirmation of purpose. I now have the opportunity to pass all of the yeses I received on to the next generation.”

Frances Lorraine Samson brought a breath of fresh air into the theater with a deceptive sense of ease in a windswept, joyful performance of the “Primavera” section of José Limón’s 1971 Dances for Isadora.

Martha Graham Dance Company artistic director Janet Eilber laughed, “So many hard acts to follow tonight,” as she took to the microphone. “But when I was asked to introduce Norton Owen, I said yes, that’s so easy, everyone knows and loves Norton, with his warm, welcoming manner, his humor, his curiosity, and how you always leave a conversation with him feeling smarter than when you started.” She spoke warmly of his long history with Jacob’s Pillow and how his interest in and devotion to the site’s archives and history led him, at a moment when American dance was finally beginning to acknowledge its own past, to define a job that didn’t exist at the time, eventually becoming the organization’s director of preservation. The Pillow’s Norton Owen Reading Room, she said, “is where they house their best interactive offering: Norton. He’s always there, ready to welcome you and to help you dive into the latest archival discovery. His work has been so inspired, and so welcoming, that he has helped the entire field celebrate and embrace its past.”

Owen shared that the Dance Magazine Awards had been on his radar since he began reading the magazine as a teenager in Alabama, and that he first attended them with his friend Bessie Schoenberg to see Hanya Holm receive her 1990 award. As he told it, Holm was at the end of the evening, which stretched quite late, and when the 97-year-old finally had her turn at the podium, he recalled, “Perhaps mindful of how long the evening was running, she got up from her seat onstage, approached the microphone with her little old lady steps, and said, ‘Thank you.’ And went back and sat down.” Owen shared how, with his mother, he got to see Natalia Markarova and Margot Fonteyn perform in Alabama, and also how Dance Magazine “captured my imagination and gave me a window on a world that existed beyond my life in Birmingham.” Jacob’s Pillow, a “dance utopia,” is every bit as magical to him today as it was when he first arrived there so many years ago. “To end on a note of gratitude,” he concluded, “as Hanya Holm said: Thank you.”

The last performance of the evening featured bassist Eduardo Bello, Music From the Sole’s Leonardo Sandoval, and 13-year-old 92NY School of Dance student Mikaylah Arce in a mesmerizing, musical melding of contemporary and tap dance. At its conclusion, Frederic Seegal presented the final award of the evening: the Chairman’s Award, which was given to dance educator, dance education advocate, and philanthropist Jody Gottfried Arnhold. “Without Jody,” he said succinctly, “I don’t think there would be dance education the way it is in New York. She is the mentors’ mentor.”

Arnhold, who received a standing ovation when she stepped onstage, said being honored in such company was “humbling. As a young dancer, waiting for the monthly delivery of my Dance Magazine was everything. I never dreamed I would one day stand here. Life is full of surprises.” She accepted the award on behalf of the 500 certified dance teachers currently teaching in New York City public schools, teaching artists, and all dance artists who find themselves working with young people. “I hear this all the time: Where is the next Alvin Ailey? Martha Graham? Paul Taylor? José Limón? I know where they are. They’re in our preK-12 public schools right now, and they deserve a dance teacher.” Sharing her journey to advocating for dance for every child in every school, she left the audience with a plea to remember one key, oft-repeated phrase: “There is no dance without dance education.”