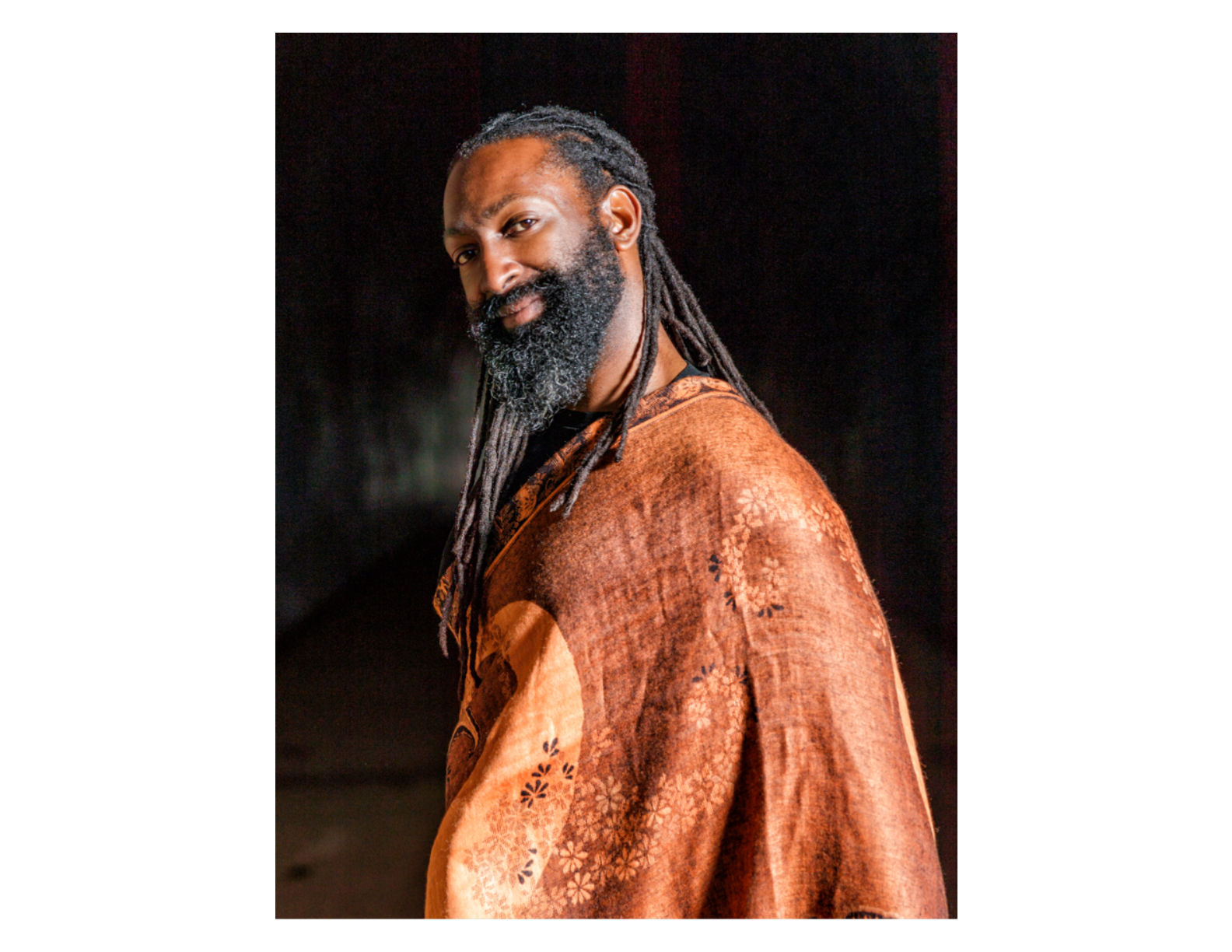

Celebrating Dance Magazine Award Honoree Antoine Hunter

This week we’re sharing tributes to all of the 2023 Dance Magazine Award honorees. For tickets to the awards ceremony on December 4, visit dancemediafoundation.org.

“Dance saved my life,” says Antoine Hunter PurpleFireCrow. Growing up in Oakland as a deeply creative Black, Indigenous, DeafDisabled person, he experienced artistic frustration and social isolation. Some parents wouldn’t let their kids play with him, while Deaf kids thought he was “too weird,” Hunter recalls. “I was all alone. I was in a dark place.” Then, in his teens, Hunter’s mother took him to see Oakland Ballet’s Nutcracker. “I realized that dance and body movement has the ability to tell a story. I can tell a story,” he said in a 2018 TEDx talk.

At first, dance didn’t seem more promising than other avenues he’d tried. In his first class at Oakland’s Skyline High School, none of the students wanted to be his partner. But with the teacher’s encouragement, he performed a solo about his longing for connection, set to Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You.” When he was done, the class burst into applause. In that moment, Hunter found a voice and a calling to elevate Deaf culture, challenge stereotypes, dismantle barriers, and empower marginalized people to claim dance for themselves.

In his choreography, Hunter melds ballet, modern, jazz, and African forms with ASL to tackle topics from ableism and racism to incarceration. “The first time I took his class was the first time I had a Deaf dance teacher,” says Zahna Simon, who joined Hunter’s award-winning Urban Jazz Dance Company in 2014 and is also its assistant director. “I felt my two worlds coming together, and it felt like home.” Hunter’s far-reaching work spans dance classes, lectures, grant-writing support, volunteering in schools, the online talk-show “#DeafWoke,” and leadership roles in organizations like the California Association for the Deaf and Bay Area Black Deaf Advocates, and much more. In 2013 he founded the Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival, which brings Deaf artists to the area for workshops, panels, museum tours, mentorship, and performances enhanced by: interpretations in multiple languages, including American Sign Language and international sign language; audio descriptions for Blind and Low-Vision audiences; and technology, such as Deaf lead devices, that allows Deaf and DeafBlind attendees to feel the music.

One of Hunter’s most compelling performances was his depiction of an incarcerated Black man in Dying While Black and Brown with San Francisco’s Zaccho Dance Theatre. “Antoine brought a humanity to the role that disarmed the audience,” says Zaccho artistic director Joanna Haigood. “He demonstrates that Deafness is not a lack of something, but a way of experiencing the world.” Hunter’s great power is channeling that lived experience into art. “Deaf people remain invisible and unheard,” he says. “Let’s listen with our heart. The bottom line is: Save lives with art.”