Is Dance “Enough” to Meaningfully Address Something Like Black Lives Matter?

2016: I was asked to create a duet for RAWdance (Ryan T. Smith and Wendy Rein) in San Francisco at a time when my heart was caught in a perpetual state of reeling from the constant murders of African Americans by law enforcement, most recently the murder of Walter Scott, who was shot in the back in South Carolina after being stopped for a nonfunctioning brake light. I knew I had to address the killings, but I didn’t know how. I felt incompetent, my work felt inadequate. So after a career dedicated to the intersection of choreography and social activism, I created Enough?, a piece that asks whether dance can meaningfully address social movements like Black Lives Matter.

1991: I was finishing Urban Scenes/Creole Dreams, my first commission for the Brooklyn Academy of Music, a work juxtaposing the early 1900s stories of my sharecropper Creole grandmother in the swamps of Louisiana with my own stories as a gay African American in New York City’s East Village at the apex of the AIDS pandemic. The work called out the sexism, racism and homophobia that extended from my grandmother’s era into my own. One night after rehearsal I participated in ACT UP’s (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) takeover of Grand Central Terminal at rush hour in order to bring that evening’s commute to its knees and force attention to America’s anemic response to the AIDS pandemic.

And take over we did. Being part of hundreds of screaming protesters taking up space in Grand Central turned an act of desperation into an act of empowerment. AIDS received the attention we demanded. What AIDS did not receive was empathy. We were hated by the understandably livid commuters; they spat at protesters, shouted AIDS-phobic slurs, and the event was one step from erupting into violence. Our protest was necessary and I was honored to be there. But I wondered what the impact might be if the commuters could deeply feel the enormity of the grief that propelled us into this takeover?

Creating this empathy was not the purpose of our takeover. But it became the purpose of my art-making. Without losing the political urgency of my work, I now wanted to create those bridges of empathy that would better transcend the boundaries of difference and allow the disenfranchised to shout tales of their personal and political histories while also allowing viewers to see themselves in the lives of these very disenfranchised. As a politics major at Princeton, I understood that a necessary first step in oppression of any kind is to dehumanize the oppressed. At that protest, my mission consciously became to “re-humanize.” Urban Scenes remained an urgent calling out of racism, sexism and homophobia, but the piece became less about those “isms” and more about the eternality of devastating loss due to those “isms.”

1991–2016: I created a body of work with this new mission at its expressive core. These works often contained text that told the nonlinear narratives of marginalized BIPOC and LGBTQ people. But it was dance’s ability to speak deeply through an abstract metaphoric language that gave these works their emotional wallop and potential to jump the boundaries between us. I knew how to speak most accessibly through text, but I knew how to speak most deeply through dance. If the goal was to create bridges, then abstract kinetic languages were the stepping-stones to those bridges. And making work in this way was enough.

Until it was not.

2022: With the advantage of time, I look back at the creation of Enough?. I had entered the studio filled with both the despair of watching the slaughter of Black bodies and the hope of watching the response by millions that became BLM, as if life were a roller coaster plummeting between heaven and hell. That roller coaster became the core of Enough?.

The piece begins with the first in a series of projected tweet-like text passages: “I have been thinking a lot about what a dance can ‘do’.” We see the performers, Ryan and Wendy, in stillness as Aretha Franklin’s rendition of “A Change Is Gonna Come” begins, a recording that is lushly beautiful even as it calls for deep change. The dancers begin one long single phrase of sumptuous movement that matches the lushness of the music. As Aretha hits a gospel-inflected high note and bends it as only Aretha can, the text passages read “YUUUUUUMMM!!” “Did your heart jump like your toes were skipping ’cross the clouds?” The intersection of words, music and dance feels sublime. The dancers repeat the same exact phrase over and over, all the while dancing faster and faster; the swirling curves of lushness slowly transform into a jagged thrashing frenzy. At the apex of this superhuman speed the intersection of words, music and dance feels like a whirlwind of despair. Media coverage of Walter Scott being shot by law enforcement is projected into the work as the core of Enough? is revealed to be a searing indictment of the murder of African Americans. The text reads “A dance can show you how my heart feels when I see that video.” “Because that video makes my heart feel like Ryan and Wendy are dancing.” “Right now.” “A dance can tell you how quickly life moves from toes touching clouds to hearts mired in hell.” Aretha’s voice ends. The only sound is the dancer’s gasping breath as Ryan and Wendy fall to the ground exhausted. The final passages of text read, “Yep, dance can do all that.” “But when I see that video, I am left to wonder…is it enough?”

Enough? altered again my choreographic tactics towards creating socially engaged choreography. The text asks whether we can act while its deeper undercurrents—the movement—insists that we must act. The “narrator” (assumedly the choreographer) is less someone to identify with than a neutral voice to propel the conversation forward. Questioning the adequacy of my own response invites you to question the adequacy of your response; our viewing the news footage “together” asks whether your heart also feels like Ryan and Wendy are dancing when you view an assault on Black bodies. Enough? does not seek empathy towards a character. It seeks empathy towards a political movement; it seeks to spur you into action not because you care about the narrator, but because you care about Walter Scott, because you care about humanity.

I went to protests. I made donations. But when I was truly lost I did the one thing I could rely on: I made a dance. Was that Enough? That is for the viewer to decide. But tapping into the immense power of performance to provoke, to prod, to move, to have heartfelt conversations in a seemingly heartless time—that felt like the most important thing I could do.

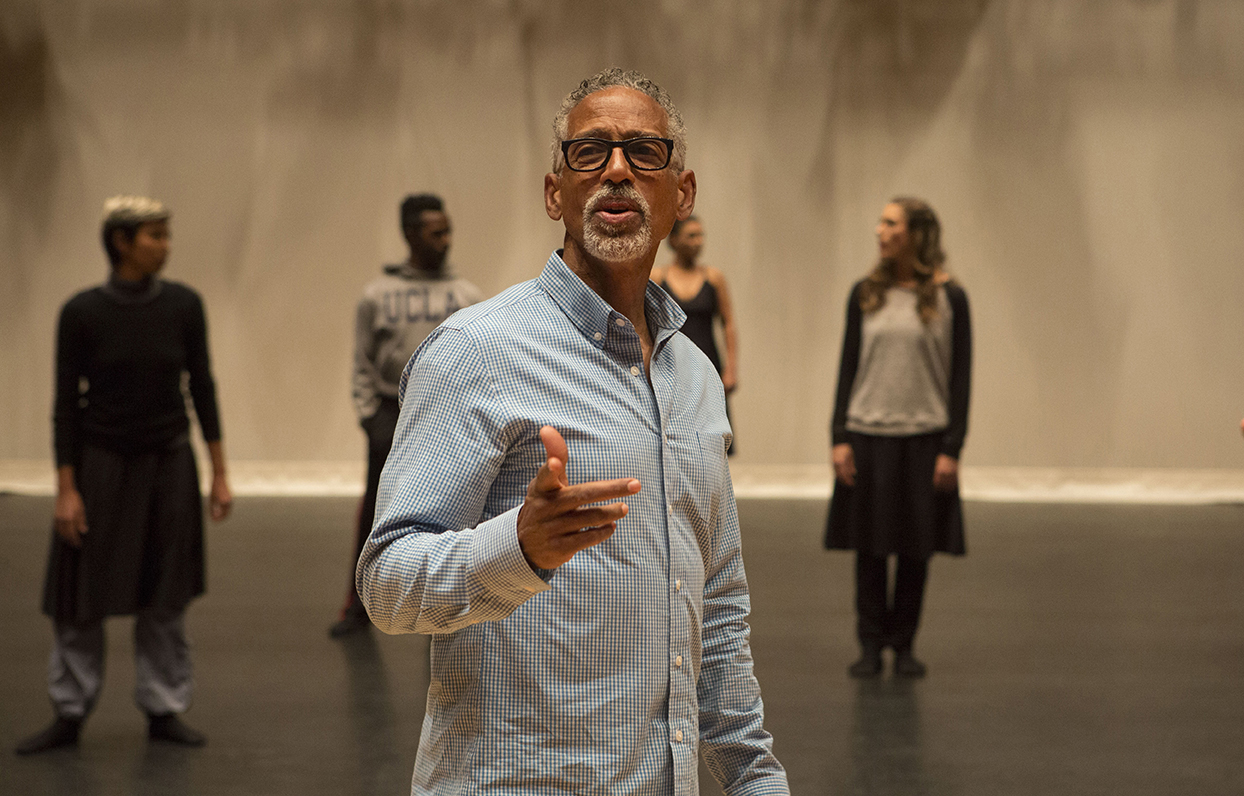

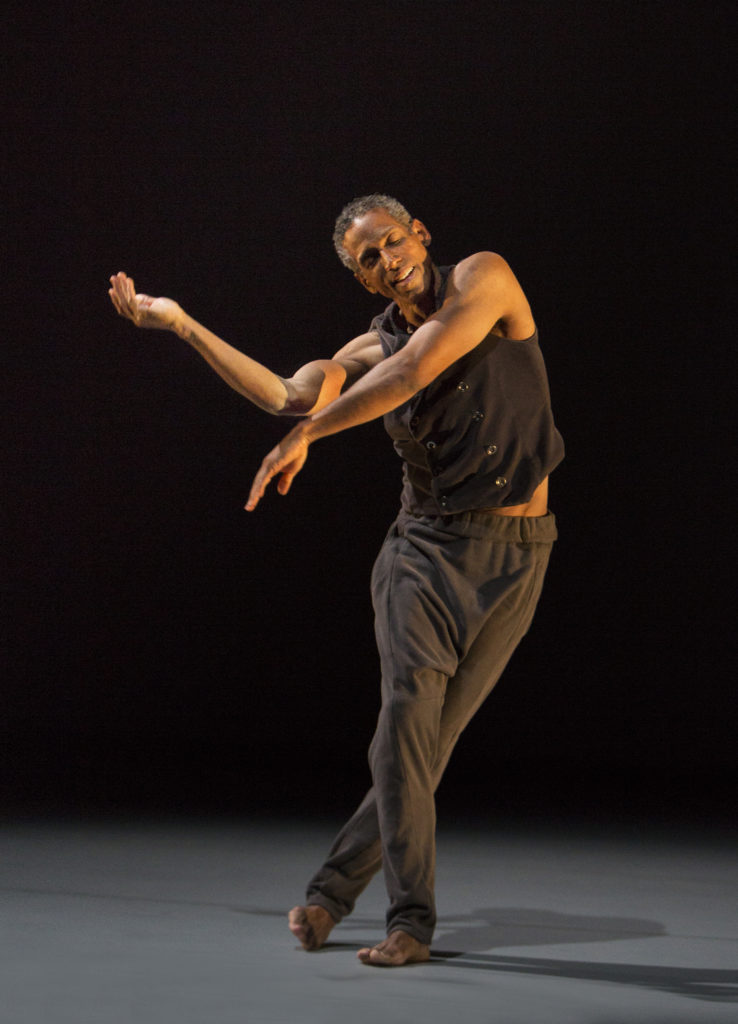

Choreographer/writer/director/filmmaker David Roussève has created 14 full evening works for his company David Roussève/REALITY.