Chloe Angyal's New Book Probes Ballet's Shortcomings—and Asks How We Can Fix Them

Chloe Angyal was best known for her incisive, feminist takes on politics and pop culture when she started writing about ballet for HuffPost in 2016. A former dancer with an undergraduate degree in sociology and a PhD in media studies, Angyal brought both an insider’s and an outsider’s perspective to her widely read articles, which connected ballet-world afflictions—sexism, racism, classism, homophobic bullying—to the larger currents shaping contemporary culture.

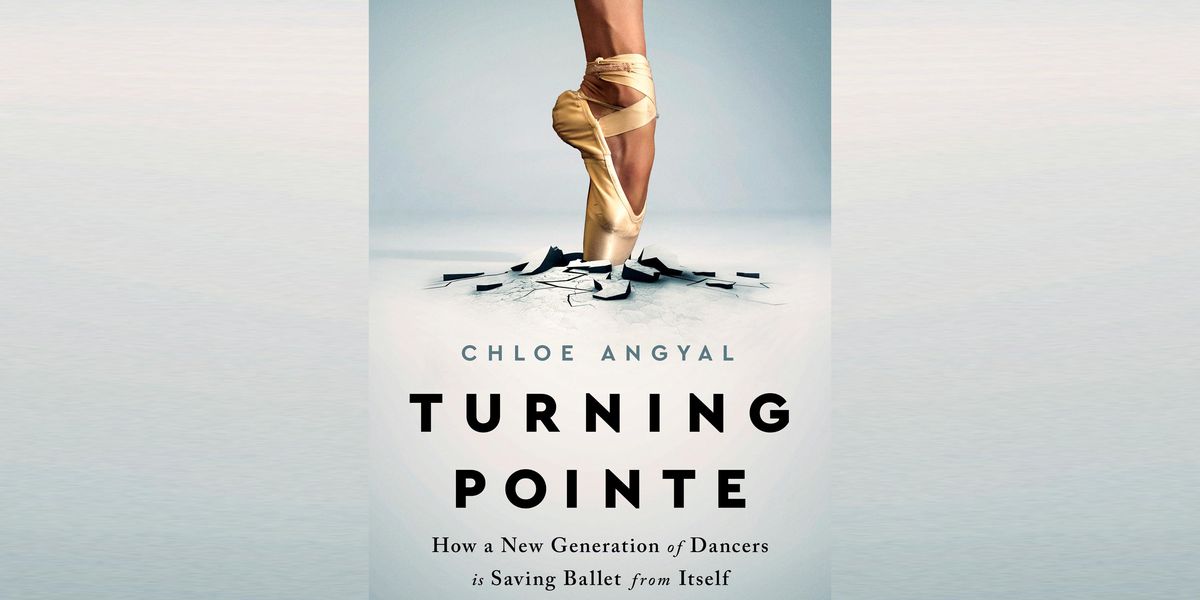

As story after story ballooned past its word count, a book idea began to take shape. Angyal’s Turning Pointe: How a New Generation of Dancers is Saving Ballet from Itself, out this month from Bold Type Books, offers a clear-eyed look at a complex, fragile ecosystem. She interviewed nearly 100 people—from pre-pointe students to artistic directors—about their love for and frustration with the art form. Ballet must change, Angyal argues, if it is to survive.

What are the big questions

Turning Pointe asks and answers?

When people ask me what the book is about, if I’m feeling punchy, I’ll just say, “Everything that’s wrong with ballet and how we can fix it.” Which is a glib way of saying, This is about a world that is ailing, and that was ailing even before the pandemic swept away so many of the familiar structures that allow it to function. This is a place where a lot of people have an experience that, if it’s not ruined by sexism, racism, classism, ableism or homophobia, it’s still shaped by those things.

You bring a sociologist’s perspective to ballet. What does that lens reveal?

There are lots of authoritative, definitive dance histories out there, which are about what happened in the past; there’s lots of great dance journalism out there, which is about what’s happening now. My sociology training allows me to sit in between those two things, to tell readers, “This is this thing that happened in 1690 that you kind of need to know to understand this other thing that’s happening now.”

Vivian Le, Courtesy Angyal

As you researched the book, what shocked you? And what

did you find least surprising?

What shocked me was the extent to which I had internalized so many of the problems in the ballet world as normal. It wasn’t until I showed the book to non-ballet people that they were able to reflect back to me, “A boss telling an employee to lose weight? Dancing on an injury? No, this is really messed up.”

What was not shocking was hearing, again and again, about the level of precarity that professional dancers live with. The combination of very limited government funding, fallible bodies and the often exploitative power imbalances—it leaves dancers spectacularly vulnerable.

That’s another idea many of us have internalized: that dancers must suffer for their art.

In a way, there’s some very cinematic glory in that. But it’s also an idea that hides all manner of exploitations: Artists are supposed to suffer, and be mad, and have tuberculosis in a garret somewhere. In truth, though, that’s a policy choice we make. It doesn’t have to be that way.

What makes you hopeful about

ballet’s future?

How much people love it. I think a lot of millennial and Gen Z dancers love ballet in an honest way, rather than a defensive way. They are comfortable holding multiple ideas in their heads at once: I love ballet, ballet needs to change.

The other thing that makes me hopeful is that I think there are people who will ultimately rupture their relationship with ballet. They will say, “This love is not worth it. I’m not being treated well in this relationship. I’m leaving.” And that’s valid too.